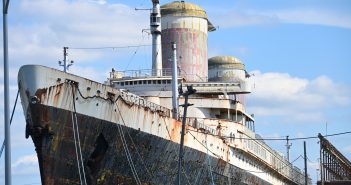

Save the United States

The right approach is to strike the very same kind of public-private partnership that birthed her to return her to passenger service.

The right approach is to strike the very same kind of public-private partnership that birthed her to return her to passenger service.

America’s biggest challenge isn’t spending; it’s that leaders are time and again paralyzed by risk aversion. Paralyzed that they will either be seen as too provocative, or paralyzed by the notion that someone, anyone, might be hurt by what they do.

As the United States seek to avert war with China, it’s vital to remember the lessons of the Falklands War. The 1981 defense cuts by the Thatcher government, including retirement of the guard ship for the South Atlantic, HMS Endurance, convinced the Argentine junta that London were no longer committed to the Falklands and their defense. As deterring war is cheaper than fighting one, Washington must avoid sending Beijing the wrong signals that could lead to miscalculation that results in conflict.

So it’s time to do more and do it increasingly quietly. Transparency has its place, but so does secrecy. Detailing what’s going to Ukraine only helps Russia better prepare for what’s coming their way, or how depleted NATO’s own stocks are becoming.

Revised on Mar 22, 2022 at 09:37 When NATO leaders meet in Brussels on Thursday,…

Washington and its allies must now regard Putin for what he is and treat him accordingly. He’s not a competitor. He’s not a potential adversary. He’s an enemy who has made his intentions clear through his words and actions.

The most important element of the agreement, however, isn’t about subs, but how quickly three allies can move to address capability shortfalls.

For many around the world, however, the events of the last week have reinforced the perception that the United States is simply not ready for prime time, whether in launching — and dragging allies into — costly, destabilizing and ultimately pointless wars, embracing questionable financial practices that plunged the world into an economic crisis, or proving unable fight a devastating pandemic that’s killed more 620,000 Americans. The world, rightly, expects the United States to do big things well, whether in crafting strategy, meaningful capabilities, starting wars or ending them.

A nation where leaders and a large chunk of the population either can’t tell fact from fiction — or deliberately won’t — can be exploited, whether internally by opportunists or externally by adversaries. This was the weakness Russia manipulated to tip the 2016 election in Trump’s favor with a disinformation campaign that cost about $100 million, the price of a single F-35 stealth fighter.

America has two years to field the capabilities needed to continue deterring an every more emboldened and capable China. Biden’s defense team will have to move fast make long-overdue changes to field new capabilities and operational concepts to maintain the nation’s deterrent edge.